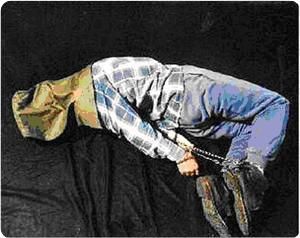

Psychiatric Expert Opinion By Graciela Carmon, M.D. Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist and PHR-Israel Board Member Originally posted by the Physicians for Human Rights-Israel at http://www.phr.org.il/default.asp?PageID=116&ItemID=1323 The purpose of this expert opinion is to address psychological and social factors that affect children and adolescents who are in custody and undergoing police interrogation. Three main questions are raised: What is the effect of police or Israeli army or other security agentsinterrogation methods on the behavior and mental state of the child or adolescent who is detained and under interrogation? What are the emotional and social consequences for the child or adolescent, and his or her family, following a traumatic interrogation experience? What are the psychological, developmental and social factors that increase the vulnerability of children and adolescents may lead to coerced false confessions? Interrogations in general are stressful situations for every person who undergoes them, but certain interrogation conditions and methods may lead to violation of the suspect’s free will, disruption of his or her mental balance, and therefore to coerced confessions. Every person in detention and under interrogation, but especially a child or adolescent, may give a false confession despite his or her innocence, in order to escape from the situation, and particularly in the following circumstances: emotional and/or physical stress, threats, mental and/or physical torture, cruel treatment, humiliation, physical and/or mental exhaustion, sleep deprivation, prolonged questioning for many hours, leading questioning, and the use deceptive and manipulative techniques (e.g. polygraph tests, providing false investigation results, fingerprints, blood, and presenting false witnesses). I would like to particularly note that severe interrogating methods such as isolation may lead to irreversible mental damage, from behavioral changes to a loss of touch with reality (a psychotic state). Following the application of such methods, the detainee feels helpless and out of control of the situation. This state of mind may lead the detainee to surrender totally to the will of the interrogators, yield to their requests and provide a confession according to their demands, a confession that will free the detainee from the interrogation. Although some detainees understand that providing a confession, despite their innocence, will have negative repercussions in the future, they nevertheless confess, as the immediate mental and/or physical anguish they feel override the future implications, whatever they may be. The groups most vulnerable to these methods of interrogation, which have a high likelihood of providing a false confession under coercion, are children and adolescents, drug addicts and/or alcoholics, and people with mental illness or mental retardation. The psychological, developmental and social factors that increase the vulnerability of children and adolescents and that may lead to false confessions under coercion · Children and adolescents have a lesser ability to endure pain and emotional and/or physical stress than adults. · In terms of psycho-biological development, the younger a child or adolescent is, the less he or she is capable of taking responsibility for his or her actions, and of analyzing complex and shifting situations. In addition, the younger the child, the more dependent he or she is. Children are incapable of objectively analyzing their actions and cannot distinguish between what they did and what they say they did. · Neuro-psychological research indicates that there are differences in maturity between a child or adolescent and an adult. Among other things, the disparity in maturity levels is apparent in the decision-making process, which is influenced by cognitive and psychological factors, together with the ability to analyze and comprehend different situations. These factors affect the ability of the child or adolescent to understand his or her legal rights and comprehend the legal process that he or she is undergoing. Many studies have shown that even in cases where children and adolescents were read their rights, they did not fully understand them or their implications. The cognitive processes of adolescents are more mature and advanced than those of children, but still do not reach maturity level of adults; therefore, adolescents also have difficulty in understanding their legal rights and the legal procedure. · Children and adolescents are more vulnerable than adults to psychological methods of interrogation. They might confess to crimes or offenses that they did not commit out of impulsiveness, fear or resignation, rather than out of a free and rational choice. · Children and adolescents are more vulnerable to methods of leading questions in an interrogation. They are more vulnerable to deception and manipulation than adults, due to their relatively short life experience, and because of their tendency to believe in the totality of authority figures, such as teachers, religious leaders, parents, doctors, and police officers. Statements such as, “I thought, because they promised me, that if I tell them things they would send me home,”[1] or, “No one told me that policemen are allowed to lie,”[2] illustrate the extent of the vulnerability of children to these methods. Since in their normative lives, children and adolescents attend establishments that are managed by mature authority figures, their natural tendency is to respond to the wishes and authority of adults. Under stress, for example in an interrogation, they lack the ability, and even the option, to object to requests or coercion by adults. · Children and adolescents are less future-oriented than adults. They take greater account of short-term than long-term consequences. Conditions of detention and interrogation for Palestinian children and adolescents • Detention without warning and/or a previous summons. • Forceful entry into the house of the child or adolescent in the middle of the night, often without a warrant, by a large number of soldiers with drawn weapons who threaten the child or adolescent and his or her family. Sometimes the soldiers wear black uniforms and their faces are covered with masks or camouflaged with makeup. The soldiers search the house, awaken its occupants, and drag the child or adolescent out of bed. • During the arrest, the soldiers employ violence against the children or adolescents who are being detained and/or their families. Many children and adolescents complain about the use of violence during the jeep ride to the interrogation facility or the wait at the military base. • The child or adolescent is placed in a jeep waiting outside, and from there is driven to a military base. There he or she is forced to wait for hours, handcuffed and often blindfolded, without food or water, and deprived of access to the toilet or a place to sleep. • Parents are not given the details of where the child or adolescent has been taken. • The detention and interrogation are undertaken in the absence of the parents. • The interrogation of the child or adolescent is performed by a number of regular police investigators, and not by certified youth investigators. • The child or adolescent is sometimes prevented from seeing an attorney during the first few days of the interrogation. • The child or adolescent is held in isolation and deprived of sleep for many hours. The consequences of the aforementioned interrogation and detention conditions for the mental well-being of Palestinian children and adolescents In traumatic conditions of interrogation and detention, like those described above, children and adolescents lose control of the situation and become particularly vulnerable, lacking internal emotional resources and external ones drawn from adult figures. Without these resources, they feel helpless and unprotected. Their vulnerability prevents children and adolescents from acting in crisis situations. They thus become apathetic and indifferent, lose their trust in adults, suffer from episodes of extreme anxiety, experience learning difficulties, and suffer from sleeping problems and nightmares. In addition, they may display severe behavioral disorders, such as aggression, over-dependence, avoidance, difficulty in returning to a routine, isolationist tendencies, and weeping. This is in addition to physical disorders, including eating disorders and bedwetting. Moreover, following the extreme humiliation and the physical and emotional stress the children and adolescents endure throughout the interrogation, they experience a profound loss of self-esteem, leading to harm to their sense of dignity and identity. I also want to emphasize the negative effects of the interrogation of children and adolescents on the family structure, since the family is left in a state of disintegration and helplessness. The adults in the family do not feel that they can provide adequate support to the children and adolescents, as they were unable to prevent their arrest and the hardships of their interrogation. The entire family structure is disrupted as a result of the undermining of the adults as a source of support and authority. Summary The violent arrest process and psychological interrogation methods mentioned above lead to the breaking of the ability of the child or adolescent to withstand the interrogation, while flagrantly violating his or her rights. These interrogation methods, when applied to children and adolescents, are equivalent to torture. These methods deeply undermine the dignity and personality of the child or adolescent, and inflict pain and severe mental suffering. Uncertainty and helplessness are situations that can too easily lead a child or adolescent to provide the requested confession, out of impulsivity, fear or submission. It is a decision that is far from free and rational choice. P. 2763/09[3]: The fact that the investigation of the appellant was conducted at 4 o’clock in the morning, immediately following his arrest, raises some difficult questions. Indeed, the law does not prohibit such an action. Previous rulings have already acknowledged the possibility that a late-night interrogation may impair the discretion of the interrogated individual... There is no doubt that these concerns grow stronger when the suspect is only a 15-year-old minor, who was only dubiously aware of his rights. It is simple to imagine what the state of mind of a child arrested in the middle of the night by soldiers, and immediately brought to a police interrogation may be... In light of the importance of these issues, and their strong influence on the protection of the rights of the detainee, which are basic, fundamental rights... it is appropriate, in my opinion, that the need to provide operative directives to the Israeli Police should be examined, if such directives do not already exist. The social and emotional consequences of the use of the aforementioned methods of detention and interrogation by the investigating and/or detaining authority for the life of the child or adolescent are difficult to remedy and damaging . They can cause serious mental suffering to a child or adolescent and cause psychological and psychiatric problem, as well as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychosomatic diseases, fits of anger, difficulties in learning and concentration, memory problems, fears and anxieties, sleep disorders, eating disorders, regressive symptoms, and bedwetting. Such outcomes are devastating to the normative development of the child or adolescent, especially when he or she is innocent. These detention and interrogation methods ultimately create a system that breaks down, exhausts and permeates the personality of the child or adolescent and robs him or her of hope. These methods are particularly harmful to children and adolescents who live in poor, isolated populations, in a state of conflict, political tension, and/or severe social stress, such as the occupied Palestinian population. The harmful effects on children can also harm the society to which they belong. Every child has the right to be a child, to his or her dignity, and to protection from all forms of violence. References · Protocols from court proceedings in cases involving children: File no. 5327/09 – Court proceeding from 21 April 2010, File no. 3599/9 – Court proceeding from 7 December 2009. File no. 3599/9 – Court proceeding from 4 January 2010. Minor arguments in case no. 1367/11 before the Hon. Judge Rivlin, from 22 February 2011. · Alayarian, Aida, MD, “Children, torture and psychological consequences,” Clinical Knowledge, vol. 19, no. 2, 2009, pp. 145-156. · Conti, Richard P., “The psychology of false confessions,” The Journal of Credibility Assessment and Witness Psychology, vol. 2, no. 1, 1999, pp. 14-36. Defense for Children International – Palestine Section,Detention Bulletin, February 2011. · Defense for Children International – Palestine Section, In their own words: A report on the situation facing Palestinian children detained in occupied East Jerusalem, 3 February 2011. · Defense for Children International – Palestine Section, In their own words: A report on the situation facing Palestinian children detained in the Israeli military court system, 29 January 2011. · Montgomery, Edith, M.Sc, Psychological effects of torture on adults, children and family relationships, 1991. · Reyes, Heman, “The worst scars are in the mind: Psychological torture,” International Review of the Red Cross, vol. 89, no. 857, September 2007, pp. 591-617. · Scott-Hayward, Christine S., “Explaining juvenile false confessions: adolescent development and police interrogations,” Law and Psychology Review, vol. 31, Spring 2007, pp. 35-76. |

~ reposted by Sofia Smith