From amidst the tear gas, a man emerges on the television screen, brandishing a weapon. Sitting atop another’s shoulders and yelling in defiant Arabic, he begins to shake the object vigorously back and forth. It is not a Molotov cocktail or a Kalashnikov. It is a placard, and on it, a cartoon of former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak’s face about to be stomped on by a shoe.

(All images courtesy Carlos Latuff)

To most around the world who watched the events of the Jan. 25 Revolution in Egypt unfold, the images of Tahrir Square protesters fleeing flanks of riot police, tear gas, and armored tanks served as vivid depictions of the egregious violence experienced directly by those on the ground. However, for those on the ground, other vivid images began to illustrate the Revolution: cartoons. These cartoons came to serve as veritable weapons as they took their place on banners and t-shirts all throughout Tahrir. The hero responsible for this cartoon arsenal doesn’t live in Cairo, or any other Egyptian city for that matter. He lives in Rio di Janeiro, Brazil, over 6,000 miles away.

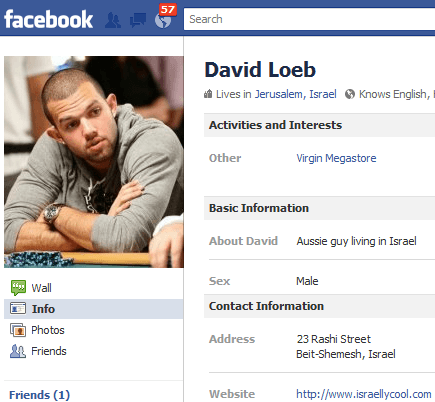

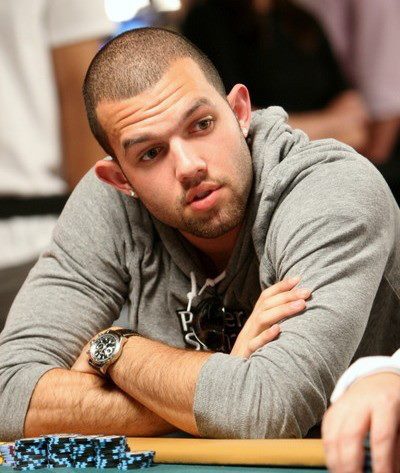

“I remember that, one day, I was watching the news on television just shortly after the Revolution began. I then saw images of people waving posters with my work appear on the screen, just days after I had made those particular cartoons. That was when I began to realize the popularity of my cartoons,” Carlos Latuff said. Latuff, a Brazilian cartoonist and self-proclaimed “artivist,” uses cartoons to expose some of the most serious instances of corruption, imperialism, and capitalist exploitation in the world today. The Jan. 25 Revolution and its aftermath have consumed Latuff’s attention and portfolio recently, and it is those pieces that have taken Latuff to a new level of international fame.

“I have long had a passion for international affairs, specifically human rights, the cowardice of states, and repression through censorship,” Latuff explained. Latuff, now in his 40s, started drawing cartoons professionally in the 1990s for Brazilian leftist trade-union newspapers, which he still works for today. In 1996, when Latuff first gained Internet access, he realized this new medium could make his work freely available to people all over the world. Stirred by a documentary he saw that year on the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, a primarily non-violent, libertarian socialist group based in southern Mexico, he decided to fax a number of his cartoons to the Zapatista political arm in Mexico City. He then drew and uploaded all of his subsequent cartoons onto the Zapatista website and permitted free dissemination of his work. Ever since, the Internet, Latuff’s “theater for virtual guerilla tactics,” has served as his gallery to the world.

He doesn’t believe in copyright, preferring “copyleft”, in keeping with his staunchly leftist leanings. Although he does not maintain a personal website, he does have a Twitpic page, and he encourages visitors to reproduce his cartoons and post them on their Facebook accounts.

***

Perhaps it comes as no surprise, then, that Latuff’s work garnered so much attention from the Egyptian people during the Jan. 25 Revolution, now commonly called the “Facebook Revolution.” The Egyptian youth who fomented and orchestrated the Revolution relied heavily on Facebook and Twitter to organize protests, coordinate platforms, and spread ideas. It was through Twitter that Latuff first came across the demands of the Egyptian Revolution, and most of the information inspiring his cartoons comes from that social media platform. “After all, the information on Twitter is coming from actual Egyptians who are tweeting right from Cairo or Alexandria, so they are in the eye of the storm,” Latuff explained.

Latuff views his cartoons as yet another weapon in a protester’s arsenal—and a more peaceful one at that. Protests continue to take place throughout Egypt to varying degrees, even nine months after the ouster of Mubarak. Men sit atop the lampposts surrounding Tahrir; women, too, amass in the square and chant in unison. All together, they voice their concerns about the incompetence of the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF), the ongoing trials of civilians in military courts, and increased media censorship, among myriad other issues. To complement these demands, protesters wave Latuff’s cartoons, such as Field Marshal Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, top officer of the SCAF, smashing an Al Jazeera video camera, or Osama Heikal, SCAF’s Minister of Information, spilling poisonous lies all over a map of Egypt. Many of Latuff’s cartoons even possess the flourish of pointed statements in Arabic, thereby evoking the true voice of the Egyptian people.

“Of course I put my own opinions into the pieces as well, but, as a human rights activist, I seek to give a voice to the voiceless, to activists in countries where they cannot speak out. For instance in Egypt, it was widely thought that after the fall of Mubarak, people would have a voice, but… we must remember that SCAF generals are the same generals that took part in the Mubarak regime,” Latuff expounded. As such, Latuff has no intention of slowing his production of Egypt-focused cartoons, which stands now at about three per week.

Latuff’s work continues to enjoy an incredible level of admiration and support among Egyptians. Over ten Facebook pages are devoted to his work. The most “liked” page boasts over 22,000 supporters, and the next two most popular pages have over 17,000 followers each. Most of these Facebook pages were started by Egyptians or others in the Middle East-North Africa region.

Two of the Facebook groups go so far as to advocate awarding Latuff with Egyptian nationality. Samar Sultan, a second-year undergraduate at the American University in Cairo, is a supporter of one of these Facebook groups. She pores over the photo albums of Latuff’s work and excitedly points out all of the nuances in his cartoons. “We don’t feel like he’s foreign, because he knows all of the Egyptian jokes. He knows all of the small details and everything,” she exclaimed, as she pauses over a caricature of Tawfiq Okasha, former member of Mubarak’s National Democratic Party. Okasha, owner of the Egyptian TV channel Al-Faraeen (“The Pharoahs”) and presidential candidate, now uses his own talk show to spout widely disdained Mubarak-era policies, and Latuff’s cartoon lampoons his personality perfectly.

Latuff’s pieces have also become well-recognized visual representations of multiple prominent human rights movements in Egypt, perhaps the most notable of which is the “We Are All Khaled Said” movement. The movement began after the eponym, a 28-year-old Egyptian from the coastal city of Alexandria, was beaten and tortured to death at the hands of two police officers on June 26, 2010. Said has since become a symbol for many Egyptians who aspire to live in a country free of brutality, torture, and ill treatment. His memory and the values that he stood for were immortalized in a prominent Facebook group, now with over 1,700,000 followers, that was started by Wael Ghonim, Head of Marketing for Google Middle East and North Africa and one of TIME Magazine’s 100 Most Influential People in 2011. Before Jan. 25, Ghonim contacted Latuff and asked him to produce some cartoons in support of the cause. Latuff responded with five cartoons, the most recognizable of which is a resolute and imposing Said holding a diminutive Mubarak by the lapel. Almost immediately after the cartoon’s release, poster upon poster of the image flooded Tahrir.

However, perhaps the most notable media endorsement in Egypt of Latuff’s work came more recently, at the end of August 2011, when Al-Masry Al-Youm, one of the most reputable newspapers in Egypt, published Latuff’s cartoon of “The Amazing Flagman” on its front page. The cartoon was created after Israeli gunfire killed five Egyptian policemen in Egypt’s Sinai. The incident served as an identifiable reason for the Egyptian people to express their disdain for the Israeli government’s policies, feelings that had been muted during the Mubarak era. At a demonstration in Cairo, 23 year-old Ahmed al-Shahat scaled the building that houses the Israeli embassy and tore down the Israeli flag, replacing it with an Egyptian one. Al-Shahat thereafter was hailed in popular media as “Flagman,” and Latuff, in keeping with his characteristically vigilant and prompt nature, provided his own creative rendition of the event within hours. “The Amazing Flagman” essentially depicted Spider Man, with the Egyptian flag’s eagle emblazoned on his uniform, descending from a building, a burning Israeli flag in hand. A day after posting the cartoon to his TwitPic page, Latuff’s site received 1.5 million views, according to Aya Batrawy of the Associated Press.

Since the Flagman episode, there have been a number of other protests at the Israeli embassy and the relationship between Egypt and Israel grows increasingly tenuous. Latuff’s marked and unabashed support of Palestinian sovereignty and his scathing critiques of the Israeli government, as depicted in endless cartoons, have won him even more popularity in Egypt. Nevertheless, as much as he would like to visit his Egyptian fans in person and set his own two feet in Tahrir, the Israeli embassy, or any of the other places he has captured in his Revolution cartoons, he doubts that he will ever get the opportunity because of his controversial opinions.

***

Latuff is not a moderate. As an ardent “artivist,” he realizes that taking a public stance on highly contentious issues won’t make everyone happy. He readily admits that although he has received an overwhelming amount of support from the Egyptian people, the occasional criticisms he hears “are to be expected.” He discerns, “The Egyptians are very nationalistic and some of them believe that someone who is not Egyptian and is drawing about Egyptian affairs could be an interference. But this… also happens when I make cartoons about Bahrain or Palestine or Iraq. My duty is not to interfere in internal affairs but to make sure a particular point of view is seen.”

Nevertheless, this strain of criticism elucidates a marked irony surrounding Latuff’s work. Latuff, in illustrating issues that span the entire globe, provides commentary on behalf of or against groups that he has personally never met. To critics, he is just penning pieces from a desk that is an ocean away from the action. In the case of Egypt specifically, he is depicting a revolution: a revolution in which heated words are exchanged, bullets fly, and lives are lost. He is providing visual images that are to speak for an entire population, or at least much of the population, and he has to demonstrate somehow a solidarity with and a keen understanding of the people on the ground without falsely representing their platform or co-opting it. That is no easy task.

And that is what underlies the great victory of social media. Latuff has been able to draw a remarkable connection with the Egyptian people—a connection through great visual imagery and culturally apposite wit—thanks to his two primary sources of information: Twitter and Facebook. Not only do these two social platforms feed him his information, but he also uses them as a dissemination tool. Moreover, news obtained from social media sites has made it possible for someone with a singular talent, like Latuff, to bolster the efforts of activists abroad. Although he is not Egyptian, and will not likely be on Egyptian soil any time soon, he is still able to follow and interact with thousands of Egyptians online, providing him with perhaps even more insight than if he were on the ground.

And yet another reason why Latuff does not fall into the role of detached artist is because Latuff is not just an artist. He is an artivist. He knows what it is like to raise issues that are obscured by one’s government and to risk one’s life in an effort to bring about a greater sense of humanity. “I have been arrested three times in Brazil for making cartoons against state and police brutality, homelessness, education, and workers’ strikes. I believe in making art for a change,” Latuff stated passionately. And that is perhaps what binds him so closely to other activists throughout the world, all waging their own battles on the human rights front, whether the battlefield is Tahrir Square in Egypt, Pearl Square in Bahrain, or Martyrs’ Square in Libya.

For right now, though, Latuff must be content with confining his own personal reach to the “public square” of the Internet. However, with close to 50,000 followers on Twitter, well over that number through various Facebook groups, and an ever-increasing fan base, his public square evades the limitations imposed by cordoned-off streets, flanks of police, and armored personnel carriers. Rather, his gallery to the world seems to be only expanding with time. The Jan. 25 Revolution—the Facebook Revolution—in Egypt is far from over, and Latuff is prepared to chronicle the Revolution in vivid color every step of the way.

Erin Biel ’13 is a Global Affairs and Ethnicity, Race, & Migration double major in Ezra Stiles College. Contact her at erin.biel@yale.edu.